BOHS IN EUROPE – THE 1970s (PART 3)

Terry Eviston, Tony Dixon and Paddy Joyce

As Bohemians look to build on last week’s positive result in Luxembourg and replicate the atmosphere created a fornight ago at the Aviva Stadium tonight, we are delighted to bring you the final part of a three-part series by GERRY FARRELL focusing on Bohemians’ experience of European football in the 1970s…

BOHS IN EUROPE – THE 1970s (PART 3)

Did you know that Karl Marx played football with the KGB in East Germany?

Bit of a trick question obviously, but there is a grain of truth in it. As Bohemian Football Club progressed to the last 16 of the European Cup, they were drawn against Dynamo Dresden, champions of East Germany and the dominant team there throughout the decade. It was a daunting mission, as we’ll see the Dresden side were packed with internationals and had reached the quarter-finals of both the UEFA Cup and European Cup within the previous three years.

Being drawn against Dynamo Dresden also meant another trip behind the “Iron Curtain”, something Bohs were getting familiar with having faced Eastern bloc sides in the past such as Polish Cup winners Śląsk Wrocław three years earlier as well as a trip to face Gottwaldov in Czechoslovakia in the club’s first-ever UEFA tie.

But returning to Karl Marx, this was the moniker given by RTÉ commentator Philip Greene when watching one of Bohs’ young stars in action. It helped that Terry Eviston played on the left-wing, and that he was fairly hirsute in those days with a mop of curly hair and a beard, not unlike the famed German political-philosopher. As for the KGB? Well, that was a joking reference to a social group of the Bohs squad who palled around together, the K-G-B stood for (Tommy) Kelly, (Eamonn) Gregg, (Joe) Burke, the defensive backbone of the successful Bohs side of the 1970s.

But before the KGB could grab a couple of German lagers, there were still some issues facing Bohemians that needed to be resolved. Having defeated Omonia Nicosia on away goals in the previous round Bohs now faced a difficult and expensive journey to Dresden, coupled with the fact the UEFA ban on using Dalymount for the home leg was still in place.

The “home” game against Omonia Nicosia had taken place in Flower Lodge in Cork City and the Bohemians directors had been busy in the meantime trying to gain permission from UEFA to host the home leg closer to Dublin. They appealed against the diktat that the game must be played 150km from Dublin and successfully reduced the distance required as part of their ban to 80km.

According to the press reports, the game in Flower Lodge, which attracted a crowd of roughly 4,500 had according to the club, cost Bohs £5,000 and, hopeful of a successful appeal, the club had already reached an agreement with Dundalk for the use of Oriel Park for the upcoming second round, first leg fixture against Dynamo Dresden.

Luckily for the club, less than two weeks before the game their appeal was granted by UEFA President Artemio Franchi. Bohs were going to Oriel Park to face Dynamo Dresden and manager Billy Young encouraged the Bohs faithful, as well as the local Dundalk population to come out in force to support Bohemians.

At the forefront of the mind for Young, and the Bohemians directors, was the issue of finance. As mentioned, the previous tie in Cork had ended up costing the club £5,000 and this, coupled with the costs of getting to Dresden was eating into the profits made from the previous year’s league win, bumper gate against Newcastle and sale of winger Gerry Ryan.

Their costs weren’t insignificant, it is worth noting that the £5,000 quoted for arranging the home tie in Flower Lodge was more than the annual salary for someone on the average industrial wage at the time. Now, thankfully with a home venue secured and the distance to travel for the home games reduced, Bohs could actually focus on the task at hand, trying to defeat Dynamo Dresden.

As for Dynamo Dresden, they had a similar result to Bohemians, losing away, but winning at home to Partizan Belgrade, but with the scores from both legs finishing at 2-0 a penalty shoot-out was required to separate the teams. Ilija Zavišić missed the decisive penalty for Partizan while Udo Schmuck proved he wasn’t that type of Schmuck by scoring his spot kick for Dresden.

It appeared that Dynamo weren’t taking Bohs lightly, in the week before the game they sent two club officials to scout on Bohs as they played Shelbourne in Tolka Park and were even planning on taping the game to analyse it.

The Irish Press reported that this would have cost the German club in the region of £1,000 and of course the Dresden officials were referred to as “spying” on Bohemians. For his part Billy Young had been in contact with Liverpool’s Bob Paisley. Liverpool had knocked Dresden out of Europe the previous season 6-3 on aggregate, winning at Anfield but losing in Dresden. Paisley noted how strong they were at home as well as commentating on Dresden’s pace, intense fitness and good technical ability.

In the opening game in Oriel Park, Bohs lined out as follows: Mick Smyth, Eamonn Gregg, Austin Brady, Tommy Kelly, Joe Burke, Pádraig O’Connor, Gino Lawless, John McCormack, Turlough O’Connor, Paddy Joyce and Terry Eviston.

The first half was fairly even as Dynamo seemed to be somewhat nervous, but as the second half progressed the East Germans began to push forward a bit more, winning a series of corners without ever really threatening Mick Smyth’s goal and being restricted to speculative long-range efforts. The media reports gave special praise to the solidity of the back four of Gregg, Burke, McCormack and Brady.

Next up, was the daunting task of the away leg. That Bohs had failed to score and hadn’t looked particularly likely to threaten, coupled with the fact that Dresden were expected to be much tougher at home meant that most commentators had understandably written off Bohs chances of progressing. The squad flew out to Dresden with a stopover in Schipol.

The overriding first impression of Dresden in October was one of greyness, modern brutalist buildings alongside memorials to the Second World War seem to be particularly striking, all those spoken to for this piece mentioned the ruins of the Dresden Frauenkirche – an 18th Century Church destroyed in the infamous incendiary bombing of the city by Allied forces in 1945 that had killed as many as 25,000 people and utterly destroyed the city. The ruins of the Church had been left as a memento to these events before eventually being reconstructed after German unification.

As for the squad’s accommodation, they were billeted in a set of holiday chalets outside of the city, usually a spot for families to flock to during the summer; they were deserted as winter approached. Crucially they were also somewhat remote and secure and were under constant armed guard. The Bohs party were assured that this was for their protection.

The squad also had official plainclothes chaperones to assist them, and keep an eye on them during their stay. Despite these efforts Terry Eviston recalls a leather jacket-clad character who approached the squad with promises to get them products of their choice in return for dollars or other western currency.

The armed guard and various official chaperones who were there to “protect” the team were by all accounts friendly enough though with limited command of English, and according to Billy Young graciously allowed the squad a bit of time to explore the city unsupervised in exchange for a bottle of Jameson whiskey.

In fact the players seem to have had plenty of freedom with Tommy Kelly, Joe Burke and Eamonn Gregg (the KGB) managing to nip out for a pint and a bite to eat a couple of days before the game to a local restaurant, only to have to hide themselves behind a curtain in an alcove in the back when Billy Young and journalist Noel Dunne walked in!

What was highly impressive though to the Bohs players and management were the facilities available to Dynamo Dresden. While the club were nominally amateurs, Dynamo being a nationwide sports club for the East German police, meant that all the players were technically policemen or working in the wider police organisation, they were for all intents and purposes professionals, in receipt of better pay, better housing, cars as well as the opportunities for international travel that came with being part of one of the states elite Fußballclubs. A designation afforded only to the elite football teams in East German.

The team played out of the 33,000-capacity Dynamo Stadion, a huge open bowl which had four iconic floodlight pylons towering above it at an angle. The stadium had medical facilities on-site as well as gyms and dormitories nearby. A far call from Dalymount despite the nominal “amateur” status of Dynamo’s players.

This wasn’t the first time that Bohs had played against German opposition in Europe, though of the Western variety, the early part of the decade had seen Bohemians face FC Köln and Hamburger SV in consecutive seasons in the UEFA Cup. As with Dresden the players were blown away by the facilities available to the German clubs, though in this case the Köln and Hamburg players were overt professional outfits.

Tommy Kelly recalled a post match meal after being knocked out of the UEFA Cup by Hamburg, opposite Tommy was the Hamburg captain and German international Georg Volkert, with little English most of the conversation was carried out through a younger Hamburg player who asked Kelly and his Bohemian teammates how much they earned. Kelly recalled that his wages at Bohs were roughly £20 a week at the time, not unusual at a club were most of the players had day jobs.

Deciding to inflate the figure he replied to Volkert that he earned £50 a week, when translated this drew surprise from Volkert who reportedly stated with a Naomi Campbell flourish, that he wouldn’t get out of bed for £50 a week. For context, it’s worth noting that three years later Hamburg would break the German transfer record to sign Kevin Keegan, offering him a better salary than he was earning at Liverpool.

Dresden were of a similar standard as those sides, six of the gold-medal winning East German squad at the 1976 Montreal Olympics were provided by Dynamo Dresden. They defeated strong (nominally amateur) sides like the Soviet Union and Poland in the semi-final and final respectively. Dresden’s star sweeper Hans-Jürgen “Dixie” Dörner was routinely described as the “Beckenbauer of the East” and eight of the side that faced Bohemians were internationals.

The differences in the home and away legs were stark. During the first half, Bohs had been solid in defence as Dynamo, cheered on by a capacity crowd who had begun flooding in hours before kick-off, had begun to exert greater and greater pressure. Bohs had been ably assisted by the oldest man on the pitch, goalkeeper Mick Smyth who had been pressed into service early and produced some remarkable saves.

However, the valiant rearguard action was finally breached by 19-year-old Andreas Trautmann in the 29th minute after a goalmouth scramble. Dixie Dörner made it 2-0 with a shot from just inside the box just before half-time and it seems that Bohs knew their race was run by that stage.

In the second half Dynamo ran riot with a goal from Schmuck, a second from Trautmann, and two penalties scored first by Dieter Reidel and then by Peter Kotte. The Irish Press ran with the questionable headline of “Dresden, left in rubble after a bombing raid in 1945 saw another blitz last night when Bohemians were ripped apart”. While the wording may have lacked sensitivity Bohs were indeed ripped apart in the second half, as can been seen even by the short clips of footage available. Dynamo Dresden can be seen moving with speed, purpose and precision as they head towards goal.

Billy Young was philosophical after the result, pointing out how well the team had done until conceding the first goal and praising the “blistering pace” of Dynamo Dresden, describing them as “undoubtedly the best side we have ever met in European competition”.

Speaking to Billy recently that is a view he still holds to this day with one exception, that of Jim McClean’s Dundee United who so impressed the Dalymount faithful when they played in Dublin in 1985. Eamonn Gregg, who had just won his third international cap a week earlier described Dresden as “better than a lot of international teams I have seen. They always seem to have two or three players in space looking for the ball”.

All that remained was the traditional post-match dinner, held in one of the fine buildings of Dresden’s old town, rebuilt after the devastation of the war, where the players were introduced to the pleasure of quail egg soup while the club were presented with painting as a memento. Young left with the quote that he felt that Bohs had “learned a lot from the game which will help us at home in the championship”.

Bohs would ultimately finish second that year, just two points behind Dundalk. This was of course the main benefit of Europe, exposure to good quality sides and new tactics and approaches as well as an excuse for a trip away and some team bonding. At the season’s close the costs of Europe were clear, the lack of proper “home” games and the cost of travel had turned the club’s financial surplus had been reduced from almost £45,000 to just under £17,000 a year later.

The second-place finish that year did, however, secure a sixth consecutive season of European football which was ended after a 2-0 aggregate defeat to Sporting Lisbon in the first round despite an impressive scoreless draw in Portugal. Bohs wouldn’t return to European competition until the infamous games against Rangers in the 1984-85 UEFA Cup.

As for Dresden, perhaps they didn’t realise it but their decade of dominance was coming to an end. Their star striker Hans-Jürgen “Hansi” Kreische, who had played in the 1974 World Cup, had retired at the end of the previous season, he had been blacklisted by the national team because he had made about who would win the 1974 World Cup.

The problem was less the bet (for five bottles of whiskey) but who he had made it with; Hans Apel, the new West German finance minister. Further fallings out with coaches and club officials at Dresden hastened his retirement aged just 30.

Apart from the loss of Kreische there was the small matter of Erich Mielke, head of the Stasi. As Dynamo were a police club they fell to an extent under his personal remit. In the 1950s Mielke had wholesale relocated the successful Dynamo Dresden squad to Berlin to play for Dynamo Berlin.

Predictably Dynamo Dresden, shorn of their title-winning players were relegated and had to spend years in the wilderness until they were promoted back in 1962. Their further development and success in the 1970s did not please Mielke who wanted a successful club in Berlin, which he eventually got. From 1978-79 Dynamo Berlin would win ten straight league titles amid much controversy and accusations of corruption, intimidating referees and preferential treatment of the club from the capital as Dynamo Berlin found themselves to be successful but also hated outside their small, devoted fanbase.

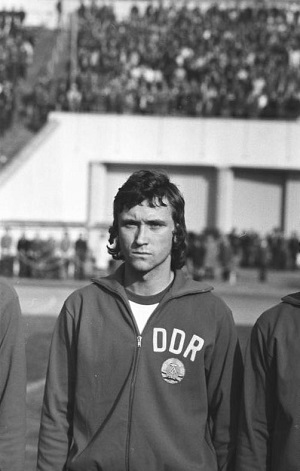

Gerd Weber

Two other players involved in the games against Bohemians had careers cut short or diminished due to political decisions, midfield Gerd Weber and striker Peter Kotte, the man who had scored the sixth and final goal against Bohemians. As Alan McDougall writes, in 1981, while waiting to travel with the East German national team to South America, Weber, Kotte and another Dresden player Matthias Müller were arrested on suspicion of Republikflucht, i.e. attempting to defect from East Germany.

Weber, a gold medal winner in Montreal, was also a Stasi informant, who sent in over 70 reports on his teammates during his time as a player. This was not uncommon and there are estimates that up to a quarter of the players and coaches of top club sides in East Germany had been recruited as Stasi informers, however Weber had apparently used a recent UEFA Cup game against FC Twente to discuss a possible defection and move to FC Köln. Kotte and Müller were accused of knowing about this plan and failing to inform the authorities.

Weber was sentenced to almost two years in prison, serving nine months, was expelled from Dynamo and from his police job, and had any other privileges that he had accrued due to his position as a well known footballer removed, and was barred from football for life. Kotte and Müller would only spend a few days in jail but they were barred from playing football in the top two divisions for life.

Peter Kotte

While Dynamo Dresden would win two more East German titles in 1988-89 and 1989-90 and even make the semi-finals of the 1988-89 UEFA Cup, the reunification of Germany was not kind to them or to any of the Eastern clubs. After early seasons in the Bundesliga, huge debts saw the club relegated to the regionalised third tier, even dropping down a level further for a time in the early 2000s. At present the club are top of the third division, hoping to be promoted back to the second tier.

Gerry Farrell